Currently I am working on a book about unfired-clay sculpture in South Asia, a genre little studied despite its presence across the region, a history reaching back at least two thousand years, and a vigorous contemporary expression, especially in Maharashtra’s Ganesh Chaturthi and Bengal’s Durga puja. During 2014-16, an Asian Cultural Council research grant has enabled me to do further research in Maharashtra, West Bengal and Bhutan. In spring of 2014 as a visiting scholar at the Yale Center for British Art, I pursued the emergence of the hyper-realistic off-shoot of the genre popular in the international exhibitions of the late 19th century. My essay, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal in the Artscape of Modern South Asia,” appeared in the Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, Rebecca Brown and Deborah Hutton, eds., 2011.

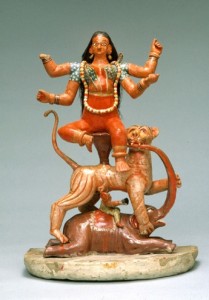

In towns and villages across the subcontinent potter-sculptors fashion sacred images – especially goddesses – from the earth. Agama texts of a millennium ago count unfired clay among the auspicious materials – along with metal, wood and stone – suitable for sacred images. Because clay is of mother earth, containing and supporting life, it is particularly suited for sacred images. Icons of unfired clay are commonly installed for the duration of a deity’s annual festival and ceremonially immersed at its close. Sometimes these images are rudimentary in form; sometimes they are exuberantly modeled. The need to make images anew for each festival allows both for the recreation of traditional forms and for innovations responding to altered circumstance.

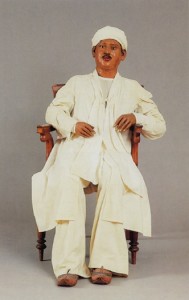

Attributed to Sri Ram Pal

Life-size Portrait of Durgaprasad Ghose (active mid 19th c), c. 1835.

© Peabody Essex Museum

In addition to images for worship, secular figures have been commonly fashioned for entertainment and instruction to be displayed during the festive season. In some centers, especially Krishnanagar-Kolkata, Pune and Lucknow, skilled practitioners adapted their technique to incorporate and enhance the ocular realism they discovered in western sculpture. Makers sculpted portraits and figures of social types, from washermen to Brahmin priests. Their success in creating life-like models attracted patronage from westerners seeking visual representation of their experience of South Asia. In the last half of the 19th century the worlds fairs of Europe and America created a demand for realistic clay figures, and displays of these became a mainstay of Britain’s installations from the colonies. The most accomplished of these “models” are forays into hyper-reality. These sculptors were instigators in the modern transformation of South Asian art practice.